How Ukrainian designers are supporting a country in crisis

by IBRAHIM

How Ukrainian designers are supporting a country in crisis

As war rages, Ukrainian designers are reorganising their work to spread messages of hope, accurate information, and provide logistical support.

On the first day of Russia’s assault of Kyiv, Ukrainian designer Alexandra Doroguntsova and her partner decided to stay in the capital city. After waking to news of the invasion, they looked out of the high-rise building – where they live with their baby – and saw endless traffic over the horizon.

“Finally the night came, and the bombing and sirens started,” she recalls. “We spent half of the night with the baby in the carpark under the building. At sunrise, I decided to just leave because it would become worse.”

She headed to Western Ukraine with her family in an attempt to find some safety. Doroguntsova is a creative director at Kyiv-based design consultancy Banda, part of Ukraine’s ever-evolving design scene. Now Banda’s 85-strong team is collaborating virtually. Though many studio members have also decided to flee Kyiv, some have remained with elderly relatives.

All commercial work has now stopped. Instead the scattered designers are working on projects that cover three main areas. One priority is creating motivational material to “keep strength inside the country – for people who are staying or volunteers”, Doroguntsova says. The second involves client-facing communication projects. Banda recently made a video calling on luxury fashion brands to stop working with Russia, for example.

Finally, the studio has been working on projects aimed at Russian civilians who seem to be “deaf and blind” to what is happening, she says. These are designed to cut through misinformation – like a pack of stickers sent to Russian women, ostensibly a celebration card but actually informing them that their soldier sons may be dead already. “They’re all really dark things, and some of them are really aggressive,” Dorogunstova adds. “But we’re trying to push all the buttons because no one really knows what’s working now.”

“Visual communication is actually about communicating things”

Iliya Pavlov moved to live and work in Austria from Kharkiv two years ago. Since the war broke out, his priority has been to get his parents out of the country; he recently met them at the Hungarian border. But his studio Grafprom – co-founded with Maria Norazian – still has offices in Kharkiv. It’s located close to the city’s main square, he explains, where a rocket recently fell. One designer was still working there, though he has now moved to the western part of the country.

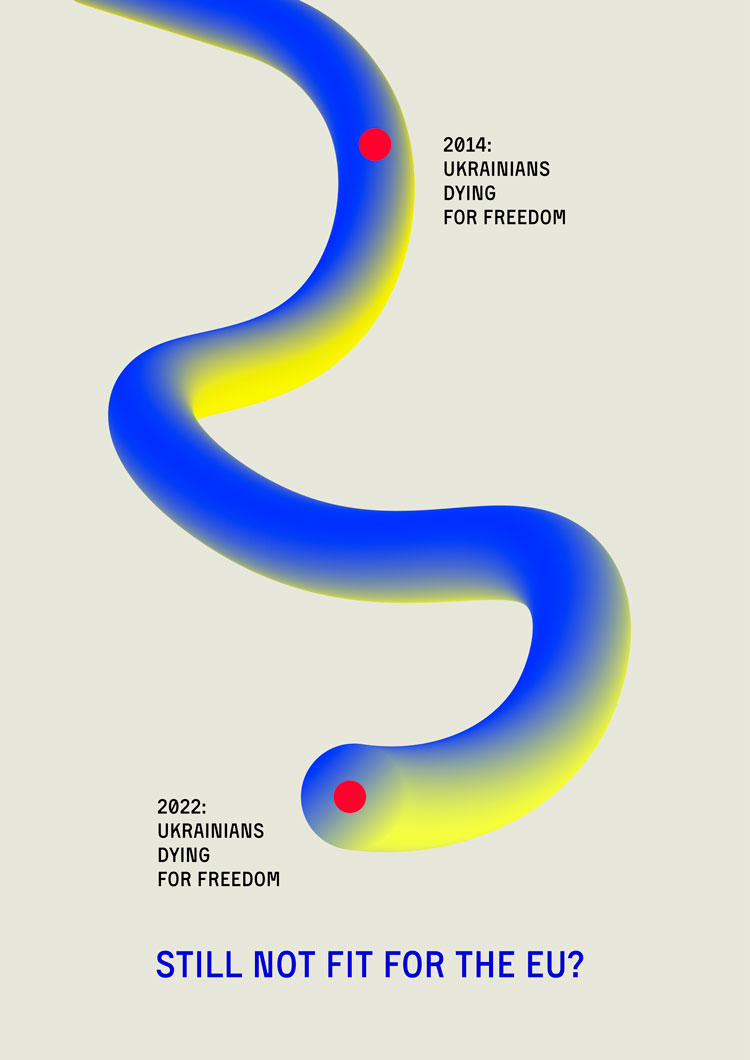

Pavlov has remained in contact with many designers back in Kharkiv. Though some have fled, others opted to remain with their families. Some have even taken up arms to defend the country, according to the designer. “People act differently,” he says simply. Pavlov himself has considered war through a design lens for some time now. He worked on a project which combined poster design and poetry when war broke out in Donbas in 2014.

Communication design on the ground in Ukraine has now come into its own, he explains. Clear and precise information is needed, as well as practical applications like wayfinding systems in the evacuation areas. “It’s been a very strong kick towards the question of the main service of visual communication,” Pavlov says. “Visual communication is actually about communicating things, not selling goods, and not making things look nice.”

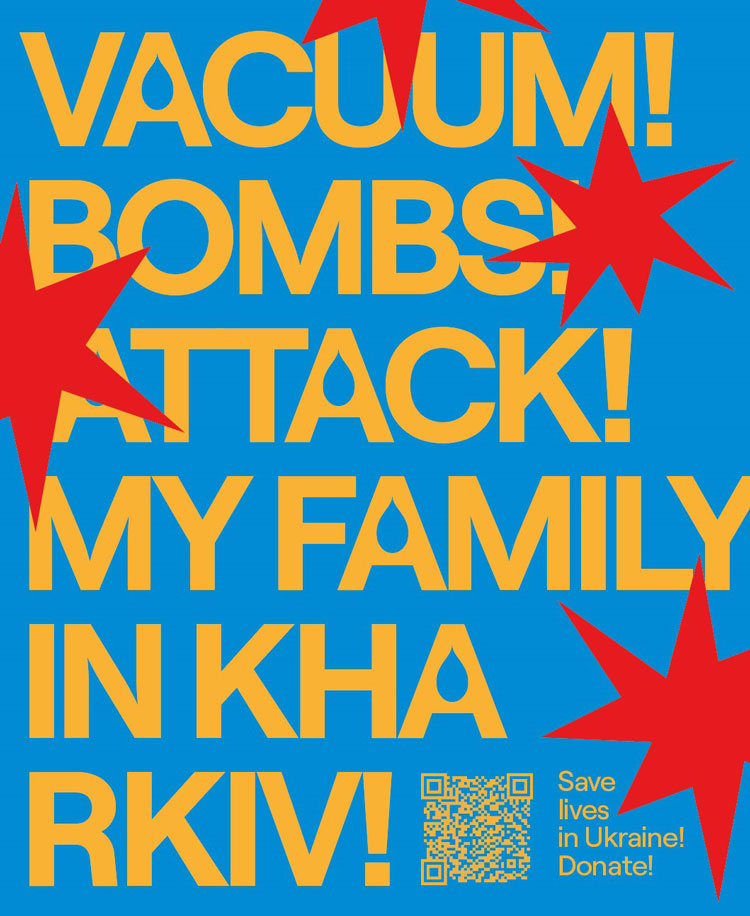

Like many designers, Pavlov has crafted posters in support of his home country. This has tied in with the 4th Block, a poster festival set up in the 90s by an association of graphic designers. This year, there’s been a focus on posters supporting Ukraine – something the association initially debated, Pavlov explains. Would it seem frivolous at a time of war? But culture is important during a time of crisis – a reminder of “what you’re fighting for”. Pavlov’s design features a QR code, which directs people to a funding site. He notes that while the codes have been around for decades, their recent resurgence has been helpful in conveying information like this quickly.

“This all is too beautiful for what is actually going on”

Posters in support of Ukraine have flooded social media feeds – often in the blue and yellow of Ukraine’s flag, usually featuring peace doves and sunflowers (the country’s national flower and now a symbol of resistance). Pavlov is conflicted about this. Many posters make “abstract or philosophical” statements, which is juxtaposed with the horrific images of the bloodshed he now regularly sees. “Poster and colours and fine typography – this all is too beautiful for what is actually going on,” he says. “Sometimes I think that the best way to communicate how horrible things are now is just to show real pictures.”

What design work is and isn’t appropriate is a thorny issue. But it’s undoubtable that many designers in Ukraine – used to pursuing creative outlets in their daily work – have found comfort in continuing their creative work. When the war first began, Kyiv-based graphic designer Katalina Maievska found she couldn’t do anything. “I was – and honestly still am – very anxious and paralysed,” she says. “I was reading a lot of news, saw more and more death, and mums giving birth to their children in the subway.”

Making visuals was a way to cope. “I paint with such aggression that my fingers hurt, because I hold my pen so strong,” she says. As well as providing a therapeutic outlet, Maievska hopes that her work will benefit others. The designer posted a link to her Instagram of her designs, in the hope that people could make T-shirts, sweatshirts, and other materials to sell. She suggests they could give money from sales to help refugees or Ukrainian troops.

She’s clear-headed about her work, which is energetic and often humorous in the face of tragedy. One poster reads: “Russian warship, go f*ck yourself”. “I’ve always wanted to be useful and make something useful – this is the main priority,” Maievska sums up. “And after that, I’ve always wanted to make beautiful things – I believe it inspires and gives pleasure to people.”

“There is still a lot of propaganda”

Ukrainian designer Yana Voko watched the war unfold from France, where she now lives. Being far from her family and loved ones prompted her to take digital action. “As a graphic designer, my first thought I had was to gather posters from Ukrainian designers, print them and just go onto the street,” Voko recalls. She initially set up a folder as part of a digital platform, but closed it as it became enormous and unruly. A member of the design community Projector neatened the idea and relaunched the resource.

The speed at which these visuals are being created and distributed speaks to the strength and collaborative nature of Ukraine’s creative community. All the designers echoed how their networks are providing financial, emotional, and logistical support – whether that’s production help for communication work or freelance job offers for displaced designers. A friend from an advertising agency had recently provided a bed for Dorogunstova’s child. International designers have also shown their support beyond posters. Pentagram’s Matt Willey designed the LT2 Stencil typeface, and 100% of profits will go to supporting Ukraine’s refugees.

For Voko, the visuals are playing a big role in spreading the Ukrainian message. “There is still a lot of propaganda or information that is not reliable enough,” she says. “For me, our role is to find mediums to catch the attention of different audiences.” That may extend to films, plays, and exhibitions in the future – she explains that there are plans for initiatives in France for documentary festivals to showcase Ukrainian directors, for example.

As the war continues, those messages will likely become more nuanced. Voko says that the world needs to know what’s going on in the actual war zone. “People have no food, no water, but they share everything between themselves,” she says. There are also topics that haven’t been touched upon; Voko points to the role of women and LGBT communities in the army. There’s also a chance, amid the tragedy, to highlight the community spirit, or as Voko puts it, “the power of people, power of cooperation, power of community, trust and love.”

Recommended Posts

NB invites local designers centre stage for Vineyard Theatre rebrand

February 24, 2023

“AI revolution” will change way design studios look within three years

February 24, 2023

Rbl rebrands ZSL with ecosystem-inspired identity

February 23, 2023